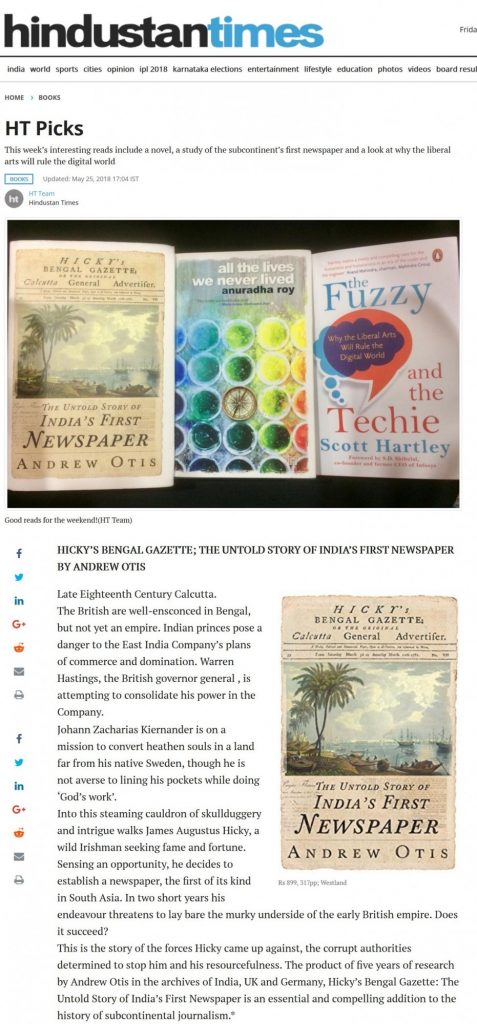

Hindustan Times, a Indian daily newspaper, selected my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper as one of their top picks.

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: Read an excerpt from a book on India’s first newspaper, the people it featured

FirstPost published an excerpt of my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

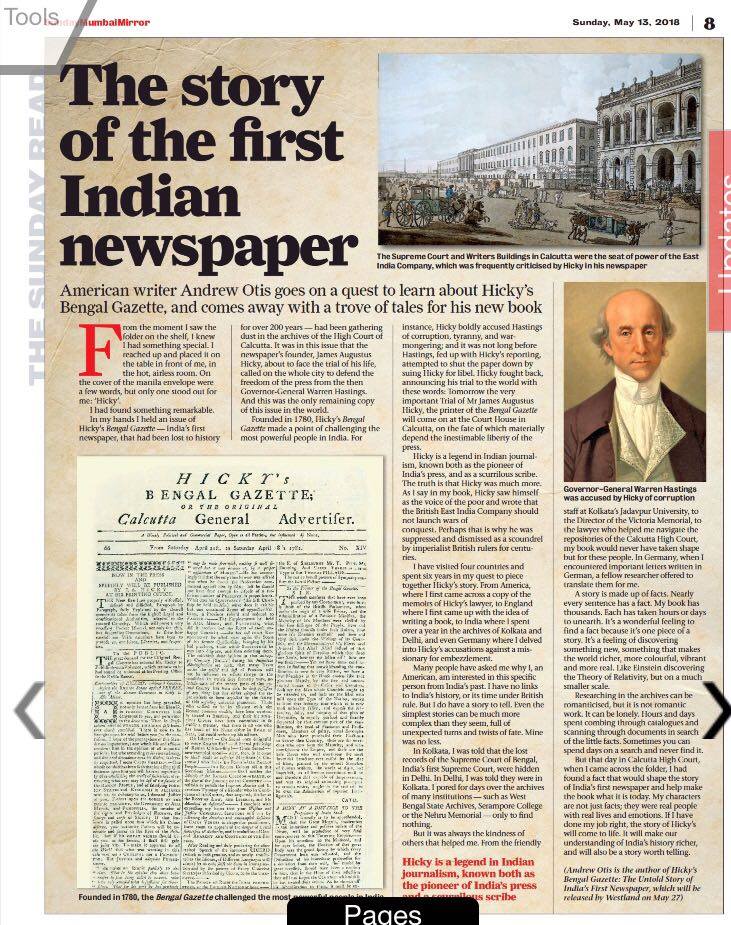

The Story of the first Indian Newspaper

I published an article (link) in the Mumbai Mirror, a leading Indian daily newspaper about my book, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

Syndicated in the Bangalore Mirror, the Pune Mirror and the Ahmedabad Mirror.

What did Hicky do after his newspaper?

Hicky was a journalist for only two years, before Governor General Warren Hastings and the Supreme Court of Bengal shut down his newspaper.

Two years is a short time. So what did Hicky do after his newspaper?

He spent the years from 1781 to 1784 in jail. Unable to pay his debts (at this time in history, prisoners had to pay for their own food and lodging in jail, leading to a vicious cycle of debt and a lifetime in prison) Hicky had no hopes of freedom.

On Christmas 1784, as one of his last acts just a month before he resigned his post as Governor General of India, Warren Hastings freed Hicky from jail. Now that the Governor General was leaving, he had nothing left to fear, should Hicky restart his newspaper.

Hicky did not restart his newspaper. He couldn’t even if he wanted to. In March 1782 – after Hicky had been in jail for nine months but was still printing his Bengal Gazette — the Supreme Court ordered the Sheriff of Calcutta to seize Hicky’s types and printing press. These were then sold at auction to, out of all people, his hated pro government rival newspaper, the India Gazette.

What Hicky did in his later years has been an enduring mystery to me, and one that I expended every effort to find out. I have followed every lead, dug deep into every archive, and searched for materials that have been lost for centuries. But I am no closer to finding out than I was when I started this project in August 2011.

All I know are the bare facts that: 1. Hicky was listed as “Dr. J.A. Hicky” in the Bengal Directory, the yellow pages of old Calcutta. 2. He had in his possession when he died large quantities of liquor and Chinese porcelain, so he was either an alcoholic or trading on the side. 3. He died on a ship going to Canton, China, backing up point two.

In 1792 Hicky posted an advertisement in the India Gazette (The same India Gazette as before, but under different management I know this because there are government records over the payment of an advertisement Hicky placed in the India Gazette. Why did he advertise? What was he advertising for? Could this be the key to unlock what Hicky was doing for the twenty years after his newspaper? Could it lead to more discoveries?

I don’t think I will ever find out. Other leads like this have also had dead ends. There are no surviving copies of the India Gazette for 1792 (that I know of). It’s another mystery that I think will never be solved.

The Missing Minutes of Calcutta’s Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of India and the Nehru Memorial.

1911 is the last date that the Minutes of the Supreme Court of Fort William, which was British India’s highest legal body from 1774-1862, are known to exist. They were transferred out of the Court, some to the Victoria Memorial. It has been my goal to find them. I believe they contain records of the trials of James Augustus Hicky, the founder of Asia’s first newspaper, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette.

I got my visa extension on Monday, August 4. On Tuesday I bought a train ticket to Delhi. On Wednesday I left, and on Thursday I arrived, dropped my bags at Johnny and Raj’s Green Park apartment and went straight to the Supreme Court of India, armed with my letter requesting permission to research in their archives.

What I found was much different than the High Court of Calcutta. In Delhi you can’t enter the Supreme Court of India’s premises without being invited in by someone inside, so I couldn’t submit my “humble petition” to the registrar personally. And therein lay the second problem: which registrar would I submit my letter to? The Supreme Court has 8+ registrars, double that number sub registrars and additional registrars to boot. Where was my letter to go and who in the Court is supposed to have authority for overseeing it?

Nevertheless, I submitted my letter and documentation to the clerks outside, and called the next to see if anyone had received it. I had already called a friend of a friend (Thank you Abhishek) who’s relative is a powerful bureaucrat and who assured me if I have any problems to let her know.

In India, there are two ways of doing anything. There’s the by-the-books follow the rules, and there’s the “who do you know.” There’s a hindi word for this “jugaar” which means “get it done.” Doesn’t matter how.

By Saturday it became apparent that no one had my letter. It was lost somewhere in the warren of paper. And on Monday, when the Court reopened I got creative. After an hour on the phone and numerous missed connections later, I was on the line with the Director of the Supreme Court’s library.

“Sure you can come in,” he said.

“But, sir, I need a photo ID pass as a guest, and I have been refused it.”

“That is no problem. Go to the Public Relations Officer and he will make you a pass. I will call him now and he will get it done.”

I arrived, the PRO summoned his officers over, they did the work quickly, and that was it. I was in.

Not knowing which way to go—for there are no signs in the Supreme Court—I picked the first staircase on the right, when up a flight, turned left, and there I was, right in front of the Library. I met with the director. He said they didn’t have the minutes.

“Is it possible to visit the archive personally?” I asked.

“No” he said

So I left, took another flight of stairs up and wandered to the end of a dead-end hallway where I saw a sign that said, “Deputy Registrar (Research). Should I go in? I thought.

I knocked and opened the door, and was greeted by an oxford educated lawyer who the Court had just brought in last month to make the process easier for researchers. This is the guy I’m looking for, I thought. A couple of phone calls later, we had the Archive/Records Room director on the line.

“Sure” he said, you can come and visit the archives.”

I went down below Court Room 5, He had my letter in front of him when I arrived. He said that the Court throws out all of its records every year, and digitizes them. Moreover, they have no records before 1937. And no records were ever transferred to the Supreme Court. (Neither the National Archives, nor the Nehru Memorial, where I also went this week have them.)

So the search for the Minutes of the Supreme Court of Judicature of Fort William continues.

Rejoice, Americans Rejoice!

When news reached Calcutta in the spring of 1780 that the American rebels/revolutionaries had signed a treaty with France, and that France would be joining the war against Great Britain, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette published the following satirical poem. Poetry was a common way of expressing political and social views in the 18th century.

It compared Americans to frogs and the French king to a stork. Americans’ initial joy would turn to sorrow, he wrote, when they realized that the French King loved nothing more than to eat frogs!

This poem is significant as a witty example of how English in another distant corner of the British Empire thought of the “treasonous” Americans.

Rejoice, Americans, rejoice!

Praise ye the Lord with heart

and voice;

The treaty’s sign’d with faithful France,

And now like Frenchmen, sing and

dance!

But when Joy gives way to reason

And friendly hints are not [akin to] treason

Let me as well as I am able,

Present your Congress with a fable.

[Tied down] with happiness, the frogs

[Sedition] croak’d through all their bogs

And then to Jove the restless race,

Made out their melancholy case

Fam’d as we are for faith, and pray’r,

We merit sure peculiar care,

But can we think great good was meant us

When legs for Governors were sent us?

With numbers crushed they fell upon,

And caused great fear; — till one by one

As courage came, we boldly faced ‘em

Then [heaped] upon ‘em, and disgraced ‘em

“Great Jove”, they croak’d, “no longer

fools us,

None but ourselves are fit to rule us:

We are too large, too free a nation,

To be incumber’d with taxation.

We pray for peace but wish confusion

Then right or wrong a revolution!

Our hearts can never bend t’obey;

Therefore no King—and more we’ll

Pray

Jove smil’d, and that to their fate resign’d

The restless, thankless, rebel kind.

Left to themselves they went to work;

First signed a treaty with King Stork,

Who swore that they with his alliance,

To all the world might bid defiance.

—Of lawful rule there was an end on it

And frogs were henceforth independent

At which the croakers, one and all,

Proclaim’d a feast and festival!

But joy today brings grief tomorrow;

Their feasting o’er, now enters sorrow

The Stork grew hungry, long’d for fish!

The Monarch could not have his wish

In rage he to the marshes flies;

And made a meat of his allies;

Then grew so fond of well-fed frogs

He made a larder of the bogs!

Say, Yankies, don’t you feel compunction,

At your unnatural, rash conjunction?

Can love for you in him take root,

Who’s Catholic and absolute?

I’ll tell these croakers how he’ll treat ‘em

Frenchmen, like storkes, love—frog

to eat ‘em.