My book was reviewed in the Indian Express.

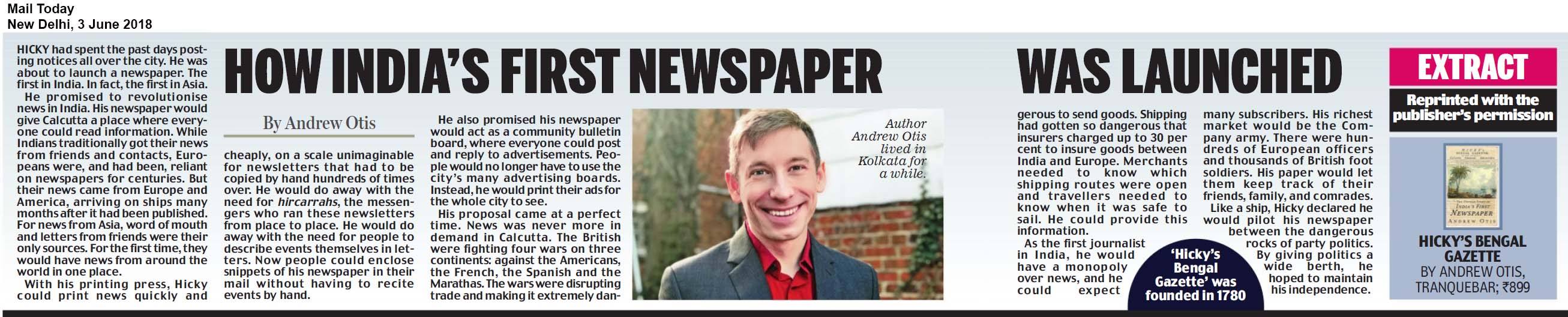

Here’s how India’s first newspaper was launched

My book was featured in Indian Today.

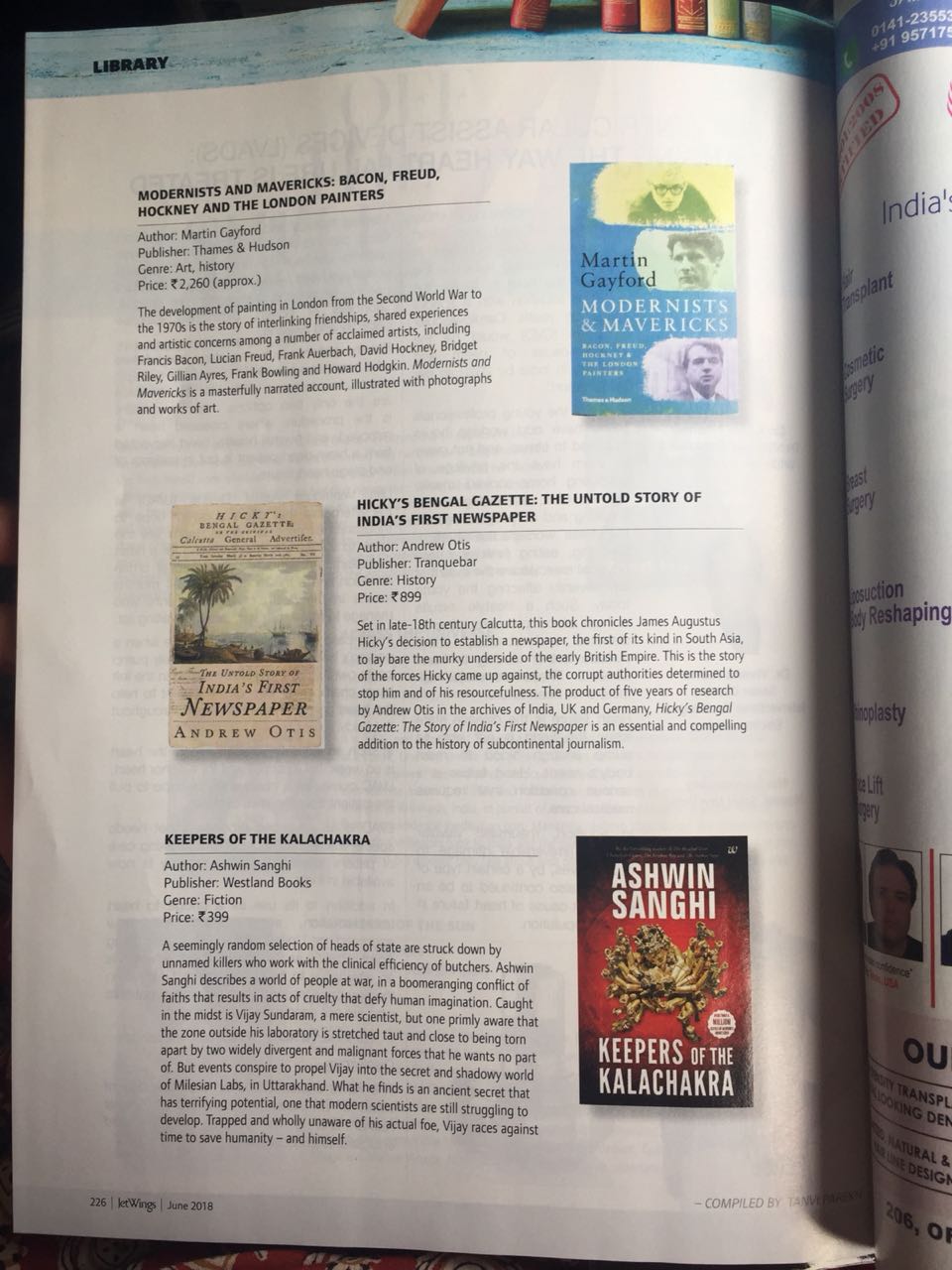

Featured in Jet Airways In-Flight Magazine

The Statesman Recommends Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper

When the Founder of India’s First Newspaper Refused to Surrender His Right to Print

The Wire published an excerpt of my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

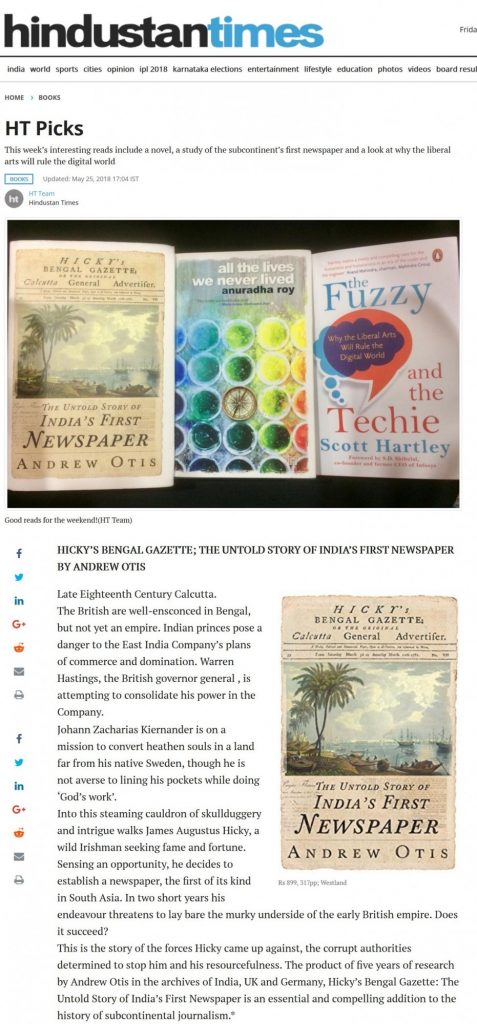

Hindustan Times Picks

Hindustan Times, a Indian daily newspaper, selected my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper as one of their top picks.

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: Read an excerpt from a book on India’s first newspaper, the people it featured

FirstPost published an excerpt of my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

The Missing Minutes of Calcutta’s Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of India and the Nehru Memorial.

1911 is the last date that the Minutes of the Supreme Court of Fort William, which was British India’s highest legal body from 1774-1862, are known to exist. They were transferred out of the Court, some to the Victoria Memorial. It has been my goal to find them. I believe they contain records of the trials of James Augustus Hicky, the founder of Asia’s first newspaper, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette.

I got my visa extension on Monday, August 4. On Tuesday I bought a train ticket to Delhi. On Wednesday I left, and on Thursday I arrived, dropped my bags at Johnny and Raj’s Green Park apartment and went straight to the Supreme Court of India, armed with my letter requesting permission to research in their archives.

What I found was much different than the High Court of Calcutta. In Delhi you can’t enter the Supreme Court of India’s premises without being invited in by someone inside, so I couldn’t submit my “humble petition” to the registrar personally. And therein lay the second problem: which registrar would I submit my letter to? The Supreme Court has 8+ registrars, double that number sub registrars and additional registrars to boot. Where was my letter to go and who in the Court is supposed to have authority for overseeing it?

Nevertheless, I submitted my letter and documentation to the clerks outside, and called the next to see if anyone had received it. I had already called a friend of a friend (Thank you Abhishek) who’s relative is a powerful bureaucrat and who assured me if I have any problems to let her know.

In India, there are two ways of doing anything. There’s the by-the-books follow the rules, and there’s the “who do you know.” There’s a hindi word for this “jugaar” which means “get it done.” Doesn’t matter how.

By Saturday it became apparent that no one had my letter. It was lost somewhere in the warren of paper. And on Monday, when the Court reopened I got creative. After an hour on the phone and numerous missed connections later, I was on the line with the Director of the Supreme Court’s library.

“Sure you can come in,” he said.

“But, sir, I need a photo ID pass as a guest, and I have been refused it.”

“That is no problem. Go to the Public Relations Officer and he will make you a pass. I will call him now and he will get it done.”

I arrived, the PRO summoned his officers over, they did the work quickly, and that was it. I was in.

Not knowing which way to go—for there are no signs in the Supreme Court—I picked the first staircase on the right, when up a flight, turned left, and there I was, right in front of the Library. I met with the director. He said they didn’t have the minutes.

“Is it possible to visit the archive personally?” I asked.

“No” he said

So I left, took another flight of stairs up and wandered to the end of a dead-end hallway where I saw a sign that said, “Deputy Registrar (Research). Should I go in? I thought.

I knocked and opened the door, and was greeted by an oxford educated lawyer who the Court had just brought in last month to make the process easier for researchers. This is the guy I’m looking for, I thought. A couple of phone calls later, we had the Archive/Records Room director on the line.

“Sure” he said, you can come and visit the archives.”

I went down below Court Room 5, He had my letter in front of him when I arrived. He said that the Court throws out all of its records every year, and digitizes them. Moreover, they have no records before 1937. And no records were ever transferred to the Supreme Court. (Neither the National Archives, nor the Nehru Memorial, where I also went this week have them.)

So the search for the Minutes of the Supreme Court of Judicature of Fort William continues.

Dakshineswar And Belur Math

Last weekend we—Carrie, Sheela and I—went to Dakshineswar (pronounced like DoKKin-swor in Bangla) and Belur Meth, two holy sites in the far north of Kolkata.

Dakshineswar was crowded and disturbing. Dead crows, security guards throwing garbage on some of the women who were cleaning it. And some very distressed, desperate people. One women was crawling along the ground inside the temple as a form of penance. I don’t think I’ve felt my whiteness as much as when a number of beggar-children approached me on the ghat outside.

We took an open ferry ride across the Hooghly from Dakshineswar. Saw a dead dog, bloated, floating down the river.

Belur Math was closed, but still, it was certainly worth taking that ferry ride.

Dakshineswar was something I’d been meaning to see for a long time, so I’m thankful Sheela took the initiative to have us see it.

Victoria Memorial Hall Research

I was looking at the Minutes for the Mayor’s Court of Calcutta at the Victoria Memorial Hall from 1748-1749 this week.

The Mayor’s Court with the Supreme Legal body in British India from the founding of Calcutta in 1690 to 1774, when the Supreme Court took its place.

The Victoria Memorial only has a couple years of the records of the Mayor’s Court. It’s now my task to find where the rest of the records are kept! Could they be in the National Archives, the High Court of Calcutta or the Supreme Court of India Museum?

Pretty cool stuff!

Trekking Sandakphu, April 20-23

At daybreak at 5am, we had beautiful views of Everest, Lhotse, Makalu and Kachenjunga, the world’s four tallest mountains (With the exception of K2 in pakistan), all around or above 8500 meters.

Our trek up Sandakphu was four days and three nights. The first day was a 17m hike from Mane Bhanjang to Tumling at 2900 meters. The second 19km stretch took us to Mt. Sandakphu, West Bengal’s tallest mountain at 3636 meters. This was not the first time I had seen these mountains, but it was by far the most amazing.

Along the way we stopped in cabins and had chow mein, momos (dumplings) and/or fried rice. The British built a rock and dirt road up to Sandakphu in the 19th century and it looks little repaired since then. It extends some 36 km up 1600 in elevation with numerous changes in elevation. We hiked that, and then down a forest of birch, rhododendron, and bamboo — traditional red panda habitat — on the third and fourth days to the town of Rimbik and then back to Darjeeling, where we were staying.

Each of the cabins had photos of white babies and cute sayings, that, or strange idyllic photoshopped posters of homes in the west, with gleaming corvettes in driveways, swans in lakes and houses covered in snow. Strange.

There is no electricity along the way but frequent way stations with squat toilets. Houses have no insulation, heat or water. Only solar electricity All is carried up by jeep. The days in April were warm but the nights frigid at high altitude. In all, the path we took saw us cross between Nepal and India four or five times. Each time we crossed into India the Indian army had us sign our names and take down our passport numbers in traditional Indian bureaucratic style. The Nepalis could care less. There were no Nepali army stations.

When we asked our guide where the Nepali army was, he said, “There is

no Nepali army.”

Unlike much of India, in the hill country, there is a blending of

Buddhist and Hindu religions. Tibetan language signs and Nepali

intermix freely, so do monasteries sit near each other.