Featured in Mathrubhumi

Mathrubhumi, the second most widely read newspaper daily in Kerala, published an article on my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

India’s first newspaper covered corruption and scandal (and sexual practices) fearlessly

I published an op-ed in Scroll.in about James Augustus Hicky and the importance of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette.

How India’s first newspaper exposed the corrupt British East India Company

Quartz India interviewed me about my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

A fine retelling of the story of James Augustus Hicky attempts, yet again, to rehabilitate the “scurrilous, wild Irishman”

My book was reviewed in the Indian Express.

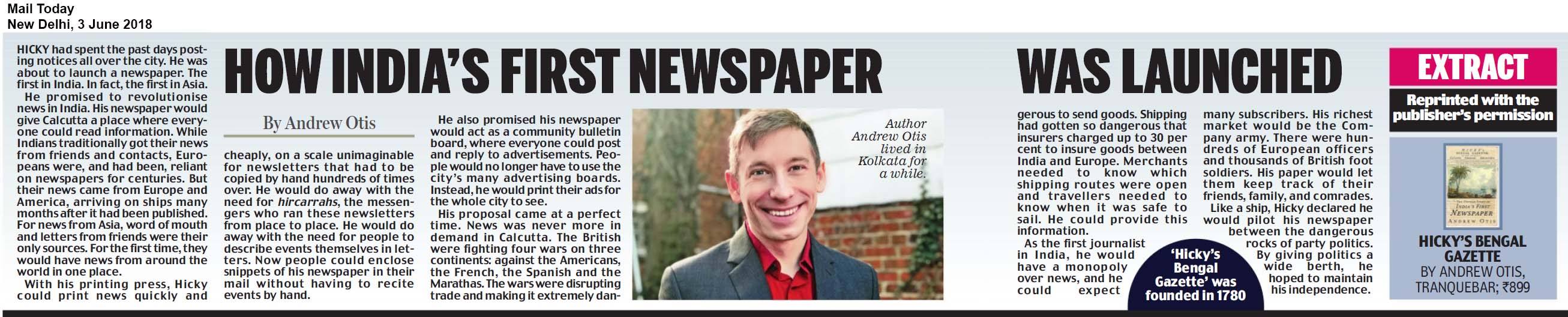

Excerpt: Hicky’s Bengal Gazette; The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper by Andrew Otis

The Hindustan Times published an excerpt of my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

Here’s how India’s first newspaper was launched

My book was featured in Indian Today.

Featured in Jet Airways In-Flight Magazine

The Statesman Recommends Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper

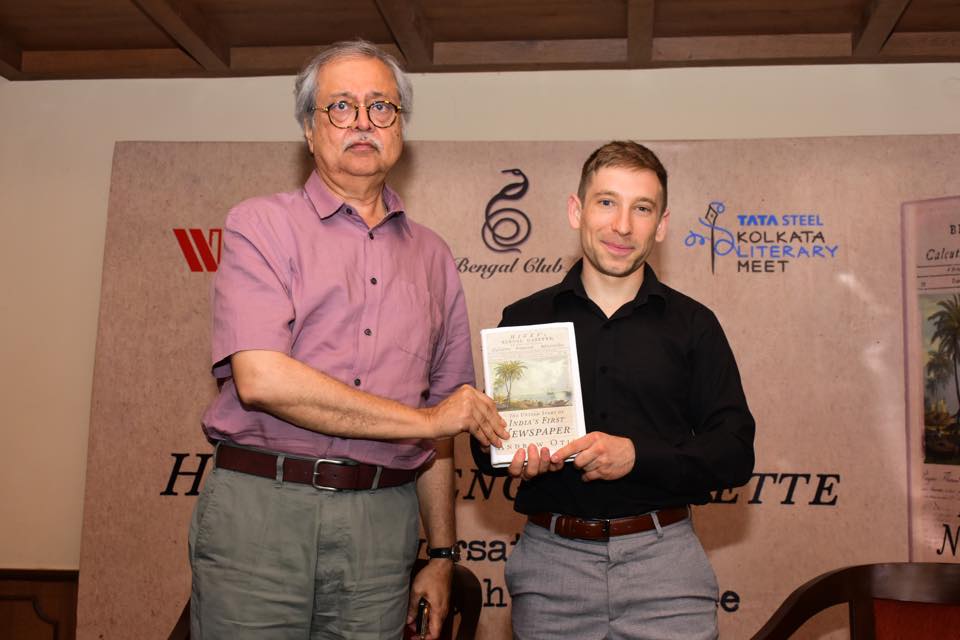

June/July Book Launch

I’m launching my book in India.

June 20 – 8 Kolkata July 20 – 22 Bombay July 22 – 30 Delhi

When the Founder of India’s First Newspaper Refused to Surrender His Right to Print

The Wire published an excerpt of my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

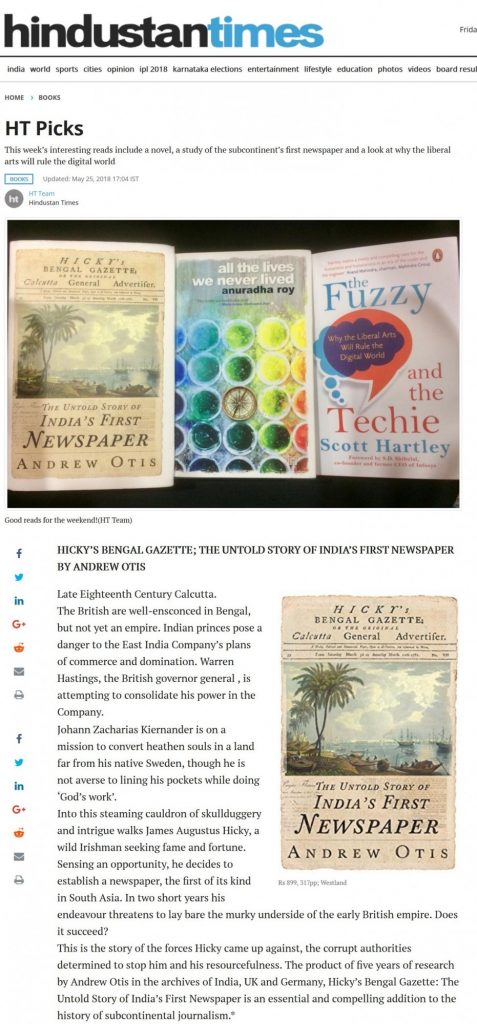

Hindustan Times Picks

Hindustan Times, a Indian daily newspaper, selected my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper as one of their top picks.

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: Read an excerpt from a book on India’s first newspaper, the people it featured

FirstPost published an excerpt of my book Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

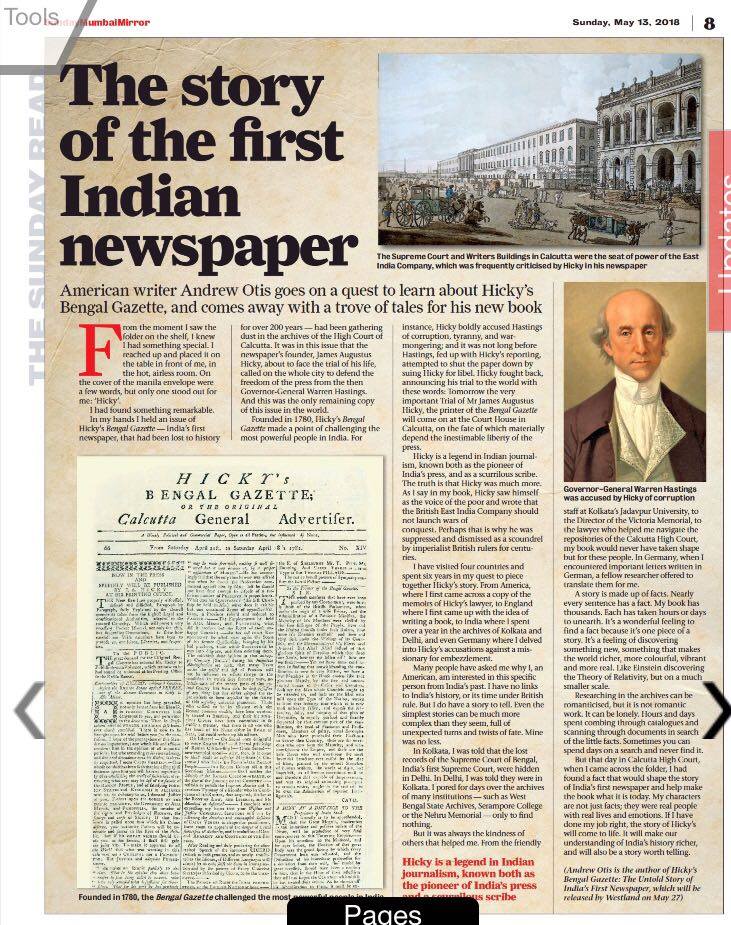

The Story of the first Indian Newspaper

I published an article (link) in the Mumbai Mirror, a leading Indian daily newspaper about my book, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

Syndicated in the Bangalore Mirror, the Pune Mirror and the Ahmedabad Mirror.

The journalist who accused Hastings of erectile dysfunction

Mid-Day, a Indian daily newspaper interviewed me about my book: Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

A History Lesson on India’s First Newspaper

On January 7, 2018, Mid-Day featured my book.

What did Hicky do after his newspaper?

Hicky was a journalist for only two years, before Governor General Warren Hastings and the Supreme Court of Bengal shut down his newspaper.

Two years is a short time. So what did Hicky do after his newspaper?

He spent the years from 1781 to 1784 in jail. Unable to pay his debts (at this time in history, prisoners had to pay for their own food and lodging in jail, leading to a vicious cycle of debt and a lifetime in prison) Hicky had no hopes of freedom.

On Christmas 1784, as one of his last acts just a month before he resigned his post as Governor General of India, Warren Hastings freed Hicky from jail. Now that the Governor General was leaving, he had nothing left to fear, should Hicky restart his newspaper.

Hicky did not restart his newspaper. He couldn’t even if he wanted to. In March 1782 – after Hicky had been in jail for nine months but was still printing his Bengal Gazette — the Supreme Court ordered the Sheriff of Calcutta to seize Hicky’s types and printing press. These were then sold at auction to, out of all people, his hated pro government rival newspaper, the India Gazette.

What Hicky did in his later years has been an enduring mystery to me, and one that I expended every effort to find out. I have followed every lead, dug deep into every archive, and searched for materials that have been lost for centuries. But I am no closer to finding out than I was when I started this project in August 2011.

All I know are the bare facts that: 1. Hicky was listed as “Dr. J.A. Hicky” in the Bengal Directory, the yellow pages of old Calcutta. 2. He had in his possession when he died large quantities of liquor and Chinese porcelain, so he was either an alcoholic or trading on the side. 3. He died on a ship going to Canton, China, backing up point two.

In 1792 Hicky posted an advertisement in the India Gazette (The same India Gazette as before, but under different management I know this because there are government records over the payment of an advertisement Hicky placed in the India Gazette. Why did he advertise? What was he advertising for? Could this be the key to unlock what Hicky was doing for the twenty years after his newspaper? Could it lead to more discoveries?

I don’t think I will ever find out. Other leads like this have also had dead ends. There are no surviving copies of the India Gazette for 1792 (that I know of). It’s another mystery that I think will never be solved.

Seeking out Justice Hyde

On July 9, 2015, the Telegraph published an article on Justice John Hyde’s legal notebooks. Hyde’s notebooks comprise one of the only remaining sources of British India’s first Supreme Court. I am working with Carol Johnson at the New Jersey Institute of Technology to decode and analyze his cipher, which he used to record intrigue and corruption during his time.

What do James Augustus Hicky and Serial have in Common?

There is an interesting part in Hicky’s trials where the Chief Justice, Elijah Impey, says to the jury in his closing remarks, “Hicky is a man among the dregs of the people. He keeps sepoys at his house.”

I have a couple problems with this:

1. These are the last words a jury is going to hear before deciding guilty or not guilty. It doesn’t sound very impartial for a Chief Justice to be calling a defendant human backwash.

2. Apparently renting out your house to dirty, smelly, scary Indians makes you a worthless human being.

This is not unusual for 18th century British India. But, imagine if a prosecutor could say today that you shouldn’t trust a defendant because they are Pakistani-American, and you just don’t know what him or his “people” could do, and the jury would believe that.

In Sarah Koenig’s podcast, Serial, about the conviction of 17 year old Adnan Sayed for murder, the prosecutor said that Adnan killed his ex-girlfriend because of his culture. “He became enraged. He felt betrayed that his honor had been besmirched. And he became very angry and he set out to kill Hae.”

This argument was backed up by a report the police commissioned from an “expert” consultant group on Islamic Thought: “It is acceptable for a Muslim man to control the actions of a woman by completely eliminating her,” read the report. “Within this harsh culture, he has not violated any code — he has defended his honor.”

The jurors said that Adnan’s religion did not affect their decision. But their statements indicated otherwise. “I’m not sure [about] the cultures over there, how they treat their women. He just wanted control and she wouldn’t give it to him,” one juror said. Another said that when the jurors were deliberating one was saying, “They were trying to talk about his culture, and Arabic culture. Men rule, not women.” (Serial, Episode 10, Around Minutes 8 – 12)

That’s just blatant racism. Also, Adnan was born and raised in Maryland.

The more involved my reading becomes, the more I see modern parallels of institutionalized racism, and how unfair nearly everything happened to be for you if you happened to be poor. You didn’t stand a chance (you still don’t really stand much chance) and no one except the disenfranchised seemed to realize this.

Mysterious Calcutta Municipal Corporation

The day before I left Kolkata, I gave a talk at Presidency University in Kolkata in which I summarized my research and the work I had been doing for 13 months in the city. It was a great presentation and I got many questions during and after it. The student and professor interest was heartening to my work. Frankly, I was surprised: who would care to show up to someone presenting on an aspect of Indian history from 200 years ago? Certainly people would have better things to do with their time.

After the talk, a number of the students from the History Department, who invited me, also invited me to have tea/coffee with them, which I gratefully accepted. We had a discussion on the comparative difficulties, opportunities and challenges of research in the US and India. It was rewarding and informative–I know little about the affects that studying at an Indian institutions would have on the ability of one to do research. The students informed me that the lack of resources and opportunities to do independent research (the expectation is less on independent research and more on classroom learning) creates mediocrity.

One of the students came to me and told me that the Kolkata Municipal Corporation indeed has an archive! I had asked through my contacts at the Fulbright Office in Kolkata who came back resolutely and said there was no archive. Now, I am upset with myself for never having gone in person to investigate, and with other people who have been too lazy to tell me they don’t know rather than to make up answers.

This has happened before though: People at the Victoria Memorial have assured me beyond any doubt that records I had been looking for were absolutely at the Supreme Court of India. But when I arrived at the Supreme Court, they said they had nothing. I can only describe it as an infuriating and painful experience to spend weeks applying to locations for permission only to realize I have been lied to because people either think they are being helpful but don’t know what they are talking about, or are too lazy to check.

What is there at the Municipal Corps Archive? Does it actually exist? What am I missing? Are the minutes of the Supreme Court there? (I am fairly confident these still exist somewhere. The British library has a few volumes, the High Court does, with maybe more in a forgotten basement, and the Victoria Memorial a few more. I find it hard to believe these have been thrown out; the British were so good with record keeping!) These are all questions I desperately want answers to, but I think only future scholars will be able to find out. My turn is over.

Nevertheless, I thank Presidency University’s student history group for their time!

Edit: Turns out the Bar Library (Room 1) of the High Court has only law reports. But they do have some very interesting, and I assume very rare booklets on the proceedings of the Sudder Dewanee Adadaults (Sadr Diwani Adalat — Indian Courts established by Warren Hastings. One of the first British attempts to standardize Hindu and Islamic justice)! There are 5 rooms in told and I need special permissions to visit each one, so I can only assume that rooms 2-5 would have more of the same. But who really knows?

The Calcutta High Court Bar Library: Under My Nose the Whole Time

I had this terrible sinking feeling that what I have been searching for the last four months – these Minutes of the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William – may have been under my nose the whole time, in the High Court of Calcutta Bar Library.

When I went into Jadavpur University on Thursday I got to see the entirety of what has been digitized of Hyde’s Notebooks, and I saw they came from the Calcutta High Court Bar Library. (I went to see what copies of Hyde’s Notebooks may contained shorthand that was not in the Microfilmed version at the National Library–and I found some!) But of course, while at the High Court, no one had told me such a thing, or that the Bar Library has old records. If the Bar Library had Hyde’s Notebooks, what else could it have?

I know these documents should still exist, but the question has always been where? Have they been thrown out or lost, or have they been at the Bar Library all along?

I go Tuesday to investigate, only two days before I leave Calcutta.

The Missing Minutes of Calcutta’s Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of India and the Nehru Memorial.

1911 is the last date that the Minutes of the Supreme Court of Fort William, which was British India’s highest legal body from 1774-1862, are known to exist. They were transferred out of the Court, some to the Victoria Memorial. It has been my goal to find them. I believe they contain records of the trials of James Augustus Hicky, the founder of Asia’s first newspaper, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette.

I got my visa extension on Monday, August 4. On Tuesday I bought a train ticket to Delhi. On Wednesday I left, and on Thursday I arrived, dropped my bags at Johnny and Raj’s Green Park apartment and went straight to the Supreme Court of India, armed with my letter requesting permission to research in their archives.

What I found was much different than the High Court of Calcutta. In Delhi you can’t enter the Supreme Court of India’s premises without being invited in by someone inside, so I couldn’t submit my “humble petition” to the registrar personally. And therein lay the second problem: which registrar would I submit my letter to? The Supreme Court has 8+ registrars, double that number sub registrars and additional registrars to boot. Where was my letter to go and who in the Court is supposed to have authority for overseeing it?

Nevertheless, I submitted my letter and documentation to the clerks outside, and called the next to see if anyone had received it. I had already called a friend of a friend (Thank you Abhishek) who’s relative is a powerful bureaucrat and who assured me if I have any problems to let her know.

In India, there are two ways of doing anything. There’s the by-the-books follow the rules, and there’s the “who do you know.” There’s a hindi word for this “jugaar” which means “get it done.” Doesn’t matter how.

By Saturday it became apparent that no one had my letter. It was lost somewhere in the warren of paper. And on Monday, when the Court reopened I got creative. After an hour on the phone and numerous missed connections later, I was on the line with the Director of the Supreme Court’s library.

“Sure you can come in,” he said.

“But, sir, I need a photo ID pass as a guest, and I have been refused it.”

“That is no problem. Go to the Public Relations Officer and he will make you a pass. I will call him now and he will get it done.”

I arrived, the PRO summoned his officers over, they did the work quickly, and that was it. I was in.

Not knowing which way to go—for there are no signs in the Supreme Court—I picked the first staircase on the right, when up a flight, turned left, and there I was, right in front of the Library. I met with the director. He said they didn’t have the minutes.

“Is it possible to visit the archive personally?” I asked.

“No” he said

So I left, took another flight of stairs up and wandered to the end of a dead-end hallway where I saw a sign that said, “Deputy Registrar (Research). Should I go in? I thought.

I knocked and opened the door, and was greeted by an oxford educated lawyer who the Court had just brought in last month to make the process easier for researchers. This is the guy I’m looking for, I thought. A couple of phone calls later, we had the Archive/Records Room director on the line.

“Sure” he said, you can come and visit the archives.”

I went down below Court Room 5, He had my letter in front of him when I arrived. He said that the Court throws out all of its records every year, and digitizes them. Moreover, they have no records before 1937. And no records were ever transferred to the Supreme Court. (Neither the National Archives, nor the Nehru Memorial, where I also went this week have them.)

So the search for the Minutes of the Supreme Court of Judicature of Fort William continues.

Rejoice, Americans Rejoice!

When news reached Calcutta in the spring of 1780 that the American rebels/revolutionaries had signed a treaty with France, and that France would be joining the war against Great Britain, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette published the following satirical poem. Poetry was a common way of expressing political and social views in the 18th century.

It compared Americans to frogs and the French king to a stork. Americans’ initial joy would turn to sorrow, he wrote, when they realized that the French King loved nothing more than to eat frogs!

This poem is significant as a witty example of how English in another distant corner of the British Empire thought of the “treasonous” Americans.

Rejoice, Americans, rejoice!

Praise ye the Lord with heart

and voice;

The treaty’s sign’d with faithful France,

And now like Frenchmen, sing and

dance!

But when Joy gives way to reason

And friendly hints are not [akin to] treason

Let me as well as I am able,

Present your Congress with a fable.

[Tied down] with happiness, the frogs

[Sedition] croak’d through all their bogs

And then to Jove the restless race,

Made out their melancholy case

Fam’d as we are for faith, and pray’r,

We merit sure peculiar care,

But can we think great good was meant us

When legs for Governors were sent us?

With numbers crushed they fell upon,

And caused great fear; — till one by one

As courage came, we boldly faced ‘em

Then [heaped] upon ‘em, and disgraced ‘em

“Great Jove”, they croak’d, “no longer

fools us,

None but ourselves are fit to rule us:

We are too large, too free a nation,

To be incumber’d with taxation.

We pray for peace but wish confusion

Then right or wrong a revolution!

Our hearts can never bend t’obey;

Therefore no King—and more we’ll

Pray

Jove smil’d, and that to their fate resign’d

The restless, thankless, rebel kind.

Left to themselves they went to work;

First signed a treaty with King Stork,

Who swore that they with his alliance,

To all the world might bid defiance.

—Of lawful rule there was an end on it

And frogs were henceforth independent

At which the croakers, one and all,

Proclaim’d a feast and festival!

But joy today brings grief tomorrow;

Their feasting o’er, now enters sorrow

The Stork grew hungry, long’d for fish!

The Monarch could not have his wish

In rage he to the marshes flies;

And made a meat of his allies;

Then grew so fond of well-fed frogs

He made a larder of the bogs!

Say, Yankies, don’t you feel compunction,

At your unnatural, rash conjunction?

Can love for you in him take root,

Who’s Catholic and absolute?

I’ll tell these croakers how he’ll treat ‘em

Frenchmen, like storkes, love—frog

to eat ‘em.

Dakshineswar And Belur Math

Last weekend we—Carrie, Sheela and I—went to Dakshineswar (pronounced like DoKKin-swor in Bangla) and Belur Meth, two holy sites in the far north of Kolkata.

Dakshineswar was crowded and disturbing. Dead crows, security guards throwing garbage on some of the women who were cleaning it. And some very distressed, desperate people. One women was crawling along the ground inside the temple as a form of penance. I don’t think I’ve felt my whiteness as much as when a number of beggar-children approached me on the ghat outside.

We took an open ferry ride across the Hooghly from Dakshineswar. Saw a dead dog, bloated, floating down the river.

Belur Math was closed, but still, it was certainly worth taking that ferry ride.

Dakshineswar was something I’d been meaning to see for a long time, so I’m thankful Sheela took the initiative to have us see it.

Murshidabad: The Versailles of Bengal

We took a right into a winding road, wide enough for one car. Brightly painted buildings on both side. We asked the nearest people, “English Cemetery?” No one knew.

As we were driving we came across a building, nearly as long as a football field. Red brick on one side. It looked like a palace, crumbling. Perhaps the cemetery was on the other side?

It was a mansion. It was huge. Painted a faint yellow and blue on the front, bleached from the sun. Two lions over the gate. We stopped and got out, and asked the people standing in front of it what it was. A palace they confirmed. People were living inside it they said. Something its size should have been in lonely planet or tripadvisor—but it wasn’t.

This Sunday we took a day trip to Murshidabad, the former capital of Bengal. We had driven since 4:30 am and arrived, after lunch at a dysfunctional restaurant, at 3:00pm. The road (National Highway 3) was more cratered pothole than road.

Then we came across the English and Dutch Cemeteries. Only 1 review in tripadvisor each. Then a tomb, small. Not in tripadvisor. Then another palace, owned by the Roy family. Not in tripadivsor. Then the Armenian lake, surrounded by walls and with a garden inside. Not in tripadivsor.

I’m amazed that Murshidabad does have the international tourist attention it should have. Its mention in lonely planet is a stub, but it’s much more to see than the Sunderbon, for instance.

When the Mughal Empire started crumbling in the 18th century, power devolved into a number of fractious princely states, ruled by Nawabs. These states still held loyalty to the Empire but it was without effect, and they ruled independently.

Bengal was one of these states. The Nawabs of Bengal ruled over the provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa (now modern day states in India). The Nawabs granted a number of trading contracts to different European East India Companies: the Dutch, French, Danish and British, and if I’m not mistaken, the Portuguese as well, though they had faded into history. Murshidabad was once a center of culture of learning, attracting communities from world wide, like the Armenians

In 1756, the Nawab, seeing the success of the most powerful of the Companies, the British, grew fearful and decided to invade. He sacked British trading “factories” and marched on Calcutta. The British fled, but came back the next year with a small, though professional army.

They retook Calcutta, advanced North to Murshidabad, and only thirty or so kilometers south of the Nawab’s capital, the two sides met in battle. With some deception—including that the British general had bribed some of the Nawab’s lieutenants, the British scored a tremendous victory, and forced the Nawab to give up all his territory. It was a momentous moment for the British Empire—and it was the most major step in the creation of British Raj, and the British dominance of India.

Murshidabad contains hidden and crumbling architecture everywhere. Tombs dot the streets, there are fantastic British and Dutch cemeteries from the European settlements at Cassimbazar (Kasimbazar). It has a beautiful riverside, clean by Indian standards. Between the river and buildings overlooking it are an endless stretch of football fields. Along the river itself are a few ghats—steps down to the water—and a lovely stretch of road with chai and ice cream stands. But it’s not crowded like I expected. There’s room to walk.

Most fantastic is the Hazar Duari—the palace of 1000 doors. Opposite it is the also impressive imambari (imam’s house). There’s also a very impressive mosque and a number of smaller palaces in different states of disrepair.

What Murshidabad lacks is development. Most of what we found was unmarked or driving on random streets. With money and time it has the right to be the tourist destination it should be.

Victoria Memorial Hall Research

I was looking at the Minutes for the Mayor’s Court of Calcutta at the Victoria Memorial Hall from 1748-1749 this week.

The Mayor’s Court with the Supreme Legal body in British India from the founding of Calcutta in 1690 to 1774, when the Supreme Court took its place.

The Victoria Memorial only has a couple years of the records of the Mayor’s Court. It’s now my task to find where the rest of the records are kept! Could they be in the National Archives, the High Court of Calcutta or the Supreme Court of India Museum?

Pretty cool stuff!

Raging Against the Raj: The First Newspaper in Asia

On June 30, 2014, Business Economics, an Indian news magazine, published an article about my research on Hicky’s Bengal Gazette and other early Indian printers.

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, the first newspaper in Asia, still remains, and will remain, incomplete.

Last month, I requested twice to digitize an issue of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette extraordinary.

I was rejected twice.

My first letter requesting permission to digitize their copies of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette was rejected. The employees of the High Court, including the lawyer who had helped me much and the assistant in the research room had declined informing me that my petition was rejected because they did not want to be the bearers of bad news—a fairly typical custom in India.

I received my rejection letter in good grace. It took the correspondence section all of 15 minutes to get it to me, which is about the quickest thing I’ve ever seen them do.

Given my rejection, I asked the research room if there was anything else I could do. One very helpful man, Hussain, in the research room provided me incredible assistance. When I explained my issue, he asked how I had gotten the British Library copy. I said they just gave it to me.

“Just it gave it to you? No formal petitions?”

“They gave it to me as a big PDF file.”

“They just let you do that?” he was shocked.

I rewrote my application, arguing that if I could digitize this copy of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette then I will be able to preserve an historical part of India’s history before it is too late. I hope this tact will grant me success. Another change in tactic is addressing the judge in a very obsequious manner. This process took the entire day, bringing me to three different offices.

My new application was 24 pages long (that includes a duplicate copy). The triplicate copy which I had printed out turned out to be unnecessary.

This was also rejected. The most frustrating part was the Research Room managerà the man who supposedly assists me in the room.

There was another court record I needed to look at. A trial in 1797 involved James Augustus Hicky versus some Bengali inhabitants who were convicted of assault and battery against him. The trial mentions Hicky’s wife. If I could find out more about her, I could understand another side of Hicky—and understand him, his wife and their family better. Perhaps she was a British woman and not a Muslim as is historically thought?

“How do you know this record exists?” he asked

“I have a source describing it”

“Ok we will need to check the catalog.”

We went to the catalog room. I told him the catalog for 1775-1800 was missing. Apparently he didn’t know that.

Then we went into the record room. This was the first time he, the research manager, entered the room. (!!!?!?!?). He turned to me, saying that he had advised the registrar that I not be allowed to digitize Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, the unsaid words being: If only he had known what was in this room, he would have submitted his opinion that I get to digitize.

On Libraries in India

I frequently say that if I were doing my research in the US and not Calcutta I could have completed my Fulbright in a month. There is much that I leave out of my blog in terms of my work and research. There is much more that simply takes time in Calcutta, from searching through archives, to gaining permissions, and to reading secondary sources for writing a book. It’s this painstaking work that is not the feature of my blog. It’s not as entertaining.

There are two copies of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette that exist in the world. For a while I thought there were actually three, after coming across a single newspaper article in 2006. The article mentioned an archive in Bhopal, India. The article said the Sapre Sangrahalaya Archive had a “treasure trove” of old newspapers and was planning on making an exhibit. After tracking down the archive, whose website was only in Hindi and whose listed phone numbers did not exist, I had my research assistant get in touch. The director did not know what they had at first.

Phone calls from three different Hindi speakers over successive days, one of whom was another American Fulbright researcher. (I shamelessly crosschecked) led me to the conclusion that the archive had only a photocopy of the front page of a March 11, 1780 edition—hardly useful.

When asked who provided that photocopy to them, the director replied, “How should I know? I wasn’t there at the time.” So much for the etymology of sources.

Many researchers have had similar issues. In fact in R. P. Kumar’s excellent article, Origin and Development of Periodicals in English in India before Independence, he noted the very poor helpfulness of libraries in India. “The response was very poor. A few librarians gave only encouragement. One of the leading librarians replied, ‘We are not going to do research for you.’”

‘We are not going to do research for you.’ When all he wanted is for them to provide a catalog. What good is a library if it does not provide a catalog?

Trekking Sandakphu, April 20-23

At daybreak at 5am, we had beautiful views of Everest, Lhotse, Makalu and Kachenjunga, the world’s four tallest mountains (With the exception of K2 in pakistan), all around or above 8500 meters.

Our trek up Sandakphu was four days and three nights. The first day was a 17m hike from Mane Bhanjang to Tumling at 2900 meters. The second 19km stretch took us to Mt. Sandakphu, West Bengal’s tallest mountain at 3636 meters. This was not the first time I had seen these mountains, but it was by far the most amazing.

Along the way we stopped in cabins and had chow mein, momos (dumplings) and/or fried rice. The British built a rock and dirt road up to Sandakphu in the 19th century and it looks little repaired since then. It extends some 36 km up 1600 in elevation with numerous changes in elevation. We hiked that, and then down a forest of birch, rhododendron, and bamboo — traditional red panda habitat — on the third and fourth days to the town of Rimbik and then back to Darjeeling, where we were staying.

Each of the cabins had photos of white babies and cute sayings, that, or strange idyllic photoshopped posters of homes in the west, with gleaming corvettes in driveways, swans in lakes and houses covered in snow. Strange.

There is no electricity along the way but frequent way stations with squat toilets. Houses have no insulation, heat or water. Only solar electricity All is carried up by jeep. The days in April were warm but the nights frigid at high altitude. In all, the path we took saw us cross between Nepal and India four or five times. Each time we crossed into India the Indian army had us sign our names and take down our passport numbers in traditional Indian bureaucratic style. The Nepalis could care less. There were no Nepali army stations.

When we asked our guide where the Nepali army was, he said, “There is

no Nepali army.”

Unlike much of India, in the hill country, there is a blending of

Buddhist and Hindu religions. Tibetan language signs and Nepali

intermix freely, so do monasteries sit near each other.