I published a guest blog with the School of African and Oriental Studies (SOAS).

Viewpoint: What India’s first newspaper says about democracy

An op-ed I wrote for the BBC (apologies for the low quality copy-original in the link).

An Unlikely Champion of Press Freedom

I wrote an op-ed for Reader’s Digest which was featured in their August edition.

India’s first newspaper covered corruption and scandal (and sexual practices) fearlessly

I published an op-ed in Scroll.in about James Augustus Hicky and the importance of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette.

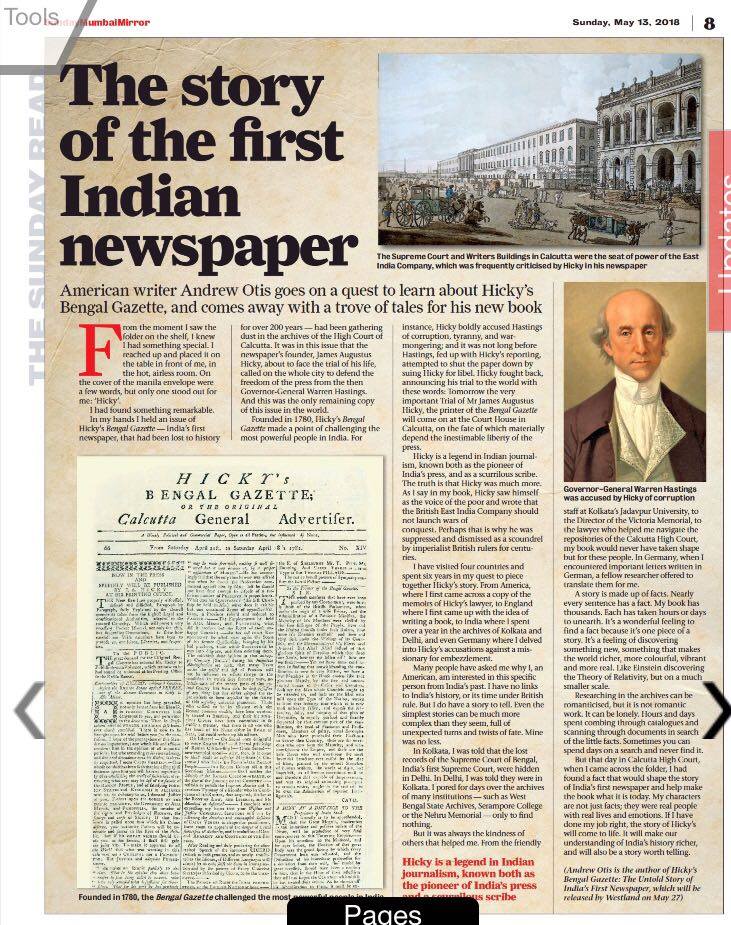

The Story of the first Indian Newspaper

I published an article (link) in the Mumbai Mirror, a leading Indian daily newspaper about my book, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper.

Syndicated in the Bangalore Mirror, the Pune Mirror and the Ahmedabad Mirror.

War Tourism in Sri Lanka

This article was featured on YAMU, Sri Lanka’s most popular culture and review website. It was written in conjunction with Sean O’Connor (Fulbright, Sri Lanka ETA 2012-2013) and was based off the authors’ first hand witnessing of war tourism in Sri Lanka’s north after a bloody 30-year civil war.

One man claims to offer every voter free ponies. Another wishes to govern on the 1611 King James Bible. What do they have in common? They’re all officially running for president, and they have the campaign songs — boom boxes included — to prove it. Reported by Andrew Otis and produced by Alexandra Dukakis. Featured on NPR Intern Edition. Photo courtesy of ibtimes.

This article was also featured in the Zimbabwean and was written about the growing refugee crisis in South Africa. It was based on a visit to De Doorns refugee camp, outside Cape Town, where one thousand five hundred people lived in canvas tents on a football field-sized patch of dirt.

This article featured in the University of Cape Town’s Newspaper, The Varsity. A version of this article was also published in the University of Rochester’s Campus Times. It is about an American’s first impressions living in Cape Town, South Africa.

Welcome to a Non-Argument

This article was featured in the University of Rochester’s Campus Times. View the original here. It is an argument rejecting the confines and constructs of typical English grammar.

Migrating South

This article was featured in the University of Rochester‘s Campus Times. View the original here. It discusses the University’s planned expansion into what were known as the UR Woodlands, a forested space south of the University. It was the first in a two part series. View the second part here.

Urban Decay, American Decay

This article was featured in Rochester’s leading daily newspaper, the Democrat and Chronicle. Unfortunately, the link to the article no longer exists. A version of this article was also featured in the University of Rochester‘s Campus Times. It describes the aesthetic death of America due to the decline of cities and the rise of suburbia.

Look on the Bright Side

This article was featured in the University of Rochester‘s Campus Times. It is general commentary on the meaning of life, with inspiration drawn from Monty Python.